Introduction

The inspiration for this project (which I completed in early 2022), was a call for applications to UC Berkeley that I came across on the topic of NLP for computational literary analysis and specifically how one might develop computational models for the plot of a novel. The brief suggests that the concept of ‘plot’ can be broken down into components such as people, places, objects, and time which could be analysed separately as part of the foundational work towards understanding plot in its entirety. I thought this would make an interesting topic to explore during the course of the Data programming in Python module for my degree.

The initial three novels I selected from Project Gutenberg for the project were:

I subsequently added a fourth book which I reserved for the evaluation phase:

Although all four books were written in the mid-19th century, each author’s backgrounds, upbringing, location and levels of maturity at the time of writing vary widely. Intuitively, it would seem that we could expect very different writing styles, vocabularies, moods, characters, and plot features in each book – and indeed if you have read the books you will know this to be true.

Background

The broad aim I had in mind was to explore the notion of “operationalizing” literary exploration (Moretti, 2013): to what extent could I develop a standardized set of techniques that would allow insights into each book individually, as well as allowing for comparison between them?

The digital humanities, and specifically computational literary analysis, is a relatively new field. Moretti, writing in 2016, reflects back on the Stanford Literary Lab trying to submit a paper on this topic to a well-known journal in 2010. The submission was rejected, and he says ‘we couldn’t help thinking that what was being turned down was not just an article, but a whole critical perspective’. Things have moved on a lot since then, and indeed the methods used in this project have almost certainly been eclipsed by the capabilities of LLMs which have subsequently demonstrated how possible the improbable is, and how genuinely useful man-machine collaborations can be.

Project aims

The project was undertaken in 2 parts:

- Data preparation, where the raw text from the books was pre-processed and the final information on chapters, paragraphs, sentences and tokens was stored in a SQL database

- Analysis & evaluation, including identifying key characters and their relative importance and placement in the novel as well as the prevailing sentiment associated with each character

Data preparation

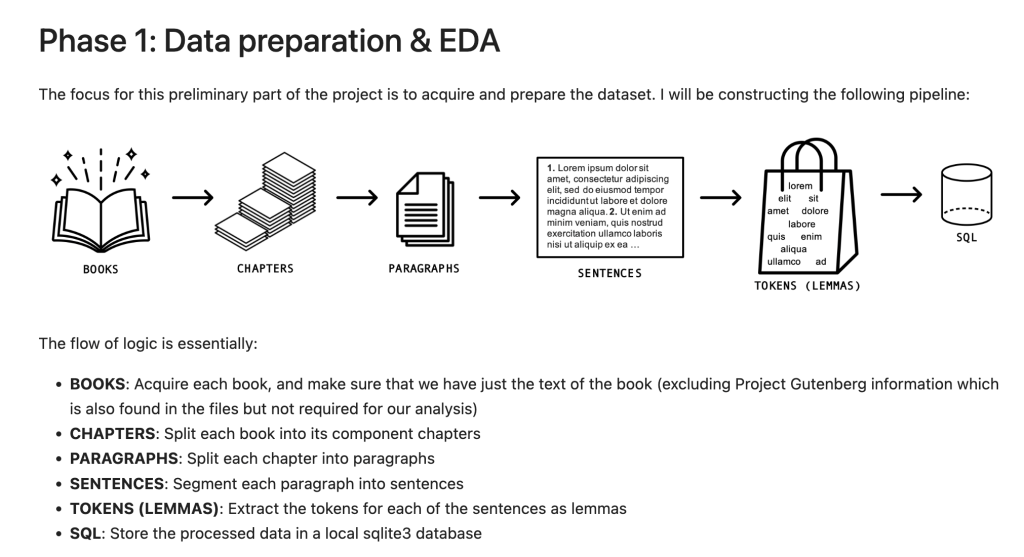

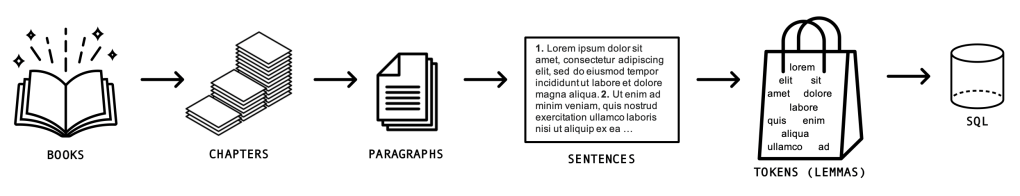

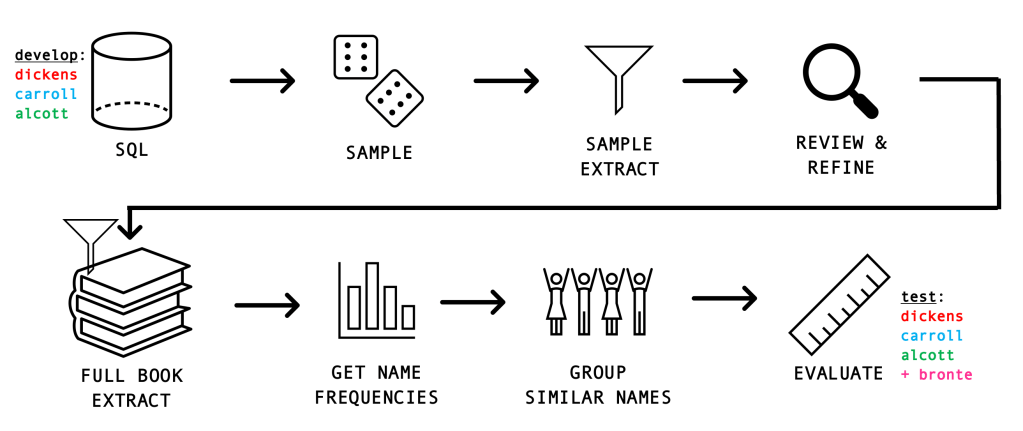

During the data preparation phase I constructed a data processing pipeline as follows:

The flow of logic was essentially:

- BOOKS: Acquire each book, and make sure that we have just the text of the book (excluding Project Gutenberg information which is also found in the files but not required for our analysis)

- CHAPTERS: Split each book into its component chapters

- PARAGRAPHS: Split each chapter into paragraphs

- SENTENCES: Segment each paragraph into sentences

- TOKENS (LEMMAS): Extract the tokens for each of the sentences as lemmas

- SQL: Store the processed data in a local sqlite3 database

This positioned me to:

- Store the pre-processed information and retrieve it as needed, when working on the in-depth analyses in the second part of this project

- Access the book structures in any way that I needed to: for example sampling from specific chapters; or retrieving individual chapters, paragraphs or sentences with thei properties, for example all sentences that reference a specific character by name

- Retrieve pre-processed data in the 2 main formats that I would need: some nlp tasks use a bag-of-words type approach (tokens), where others require the full sentence for context

- Compile and store additional resources required for further analysis, such as vocabulary counts

The concept was simple enough: I could query the database directly for quick checks and aggregations, or I could read in results as a dataframe and continue working where I left off.

Analysis & evaluation

Identifying key characters

Identifying characters is an information extraction task in natural language processing (NLP). This was the heart of my project and potentially the hardest task. My objectives here were two-fold:

- Identify character names in each book

- Identify as many mentions of each of these characters as possible within each book

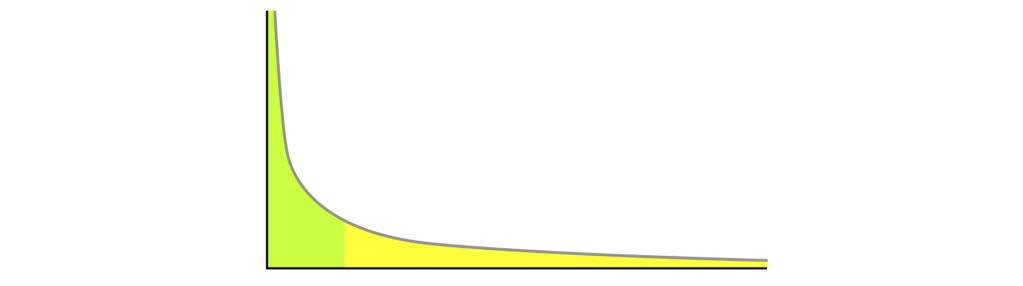

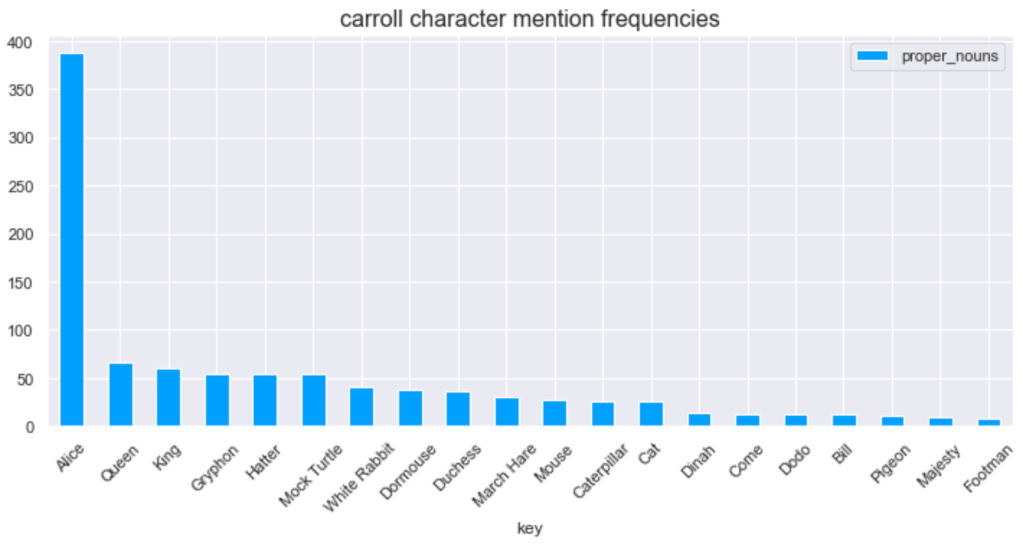

Sack (2011) looked at character ‘mention’ frequencies in a set of sixty 19th century British novels and noted that character frequencies often showed a long-tailed distribution – which makes sense: main characters will be mentioned more frequently than incidental ones (with the possible exception of books written in the first person). If this assumption held true for our books (which it turned out it did), then ideally I wanted to have extracted most of the characters occupying the green area shown below and these should represent the main characters of interest.

Vala, et al.(2015) wrote an amusingly-titled paper on this subject (Mr. Bennet, his coachman, and the Archbishop walk into a bar but only one of them gets recognized: On The Difficulty of Detecting Characters in Literary Texts) in which they conclude that identifying all characters in a novel still presented a significant challenge at the time of writing.

In my task of identifying the main characters, I loosely based my algorithm on some of the techniques discussed by Vala and Sack, including using named entity recognition and proper noun identification as a foundation, leveraging the long-tailed distribution of characters, and grouping similar names as far as possible. The following provides an overview of the process followed:

- Retrieve the pre-processed book data from our SQL database

- Obtain a stratified sample (so that each book length remains representative)

- Do an initial pass to extract named entities / proper nouns

- Review the outputs and identify any refinements we can make to the process to improve results

- Extract named entities / proper nouns from the full books

- Get name frequencies from the resulting data

- Group similar names in an attempt to see if we can resolve similar character names like Queen and Queen of Hearts

- Evaluate the results

Named entity recognition (NER)

Named entity recognition identifies sequences (or spans) of proper nouns and then labels them by category, for example person, location, organization, date, and so on. Jiang, et al. (2016) conducted a comparison of 4 mainstream NER tools: NLTK, spaCy, Alias-i LingPipe NER and Stanford NER. They found that Stanford NER and spaCy performed best overall on their chosen WikiGold dataset.

I investigated 2 of these tools:

- NLTK

- spaCy (en_core_web_sm)

I excluded Alias-i LingPipe NER and Stanford NER from my investigation in the interests of time and complexity (additional downloads and the installation of Java in the environment would have been required).

The advantage of using standard NER techniques was that I could get the entity labels so I could easily specify that we wanted ‘just people’. However, the performance of NER is very much affected by the corpus on which the model was trained and the writing style and content of our 19th century novels is rather different from typical corpora like OntoNotes (Weischedel, et al., 2013) on which spaCy is trained (spacy.io, 2022) – which include news articles, conversations and blogs. This did seem to have an effect on performance, particularly when it came to recognizing titled names like Mr. Pip.

Proper noun chunking with WordNet location lookup

Since the foundation of named entity recognition is noun phrase chunking (Bird, et al., 2009) I thought it would be interesting to try extracting characters with this simpler method, using the NLTK library.

The advantage of this method is that, being simpler, it can be more robust. On the other hand, it does return rather more noisy results including place names, organizations, products and the like. In documents like news articles this would be a real issue. However, in novels I worked on the simplifying assumption that most of this noise will occur lower down in the list of entities: the most frequent proper nouns we’ll encounter will be people, followed by places. If this assumption holds true then the majority of the proper nouns near the top of the list will be characters.

Location is often quite an important element in novels too of course, so I used Wordnet (Princeton University, 2010) to check for and remove place names. Wordnet is a lexical database for English: ‘Nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs are grouped into sets of cognitive synonyms (synsets), each expressing a distinct concept‘, and these synsets form a hierarchy of hyponyms (lower-level concepts) and hypernyms (higher level concepts). Using the hypernym ‘location‘ I could look for hyponyms lower down in this hierarchy and discard them as known locations. As an aside, one could argue that if a place name looms so large in a novel that it’s one of the top names, one could almost consider it a ‘character’ of sorts – but that is a debate for a different day!

Refining and grouping

Since I was not aiming to extract every single character, just the main players, I investigated ways to reduce the initial set of names extracted and just retain the most important ones. And finally I looked at grouping similar names – for example, if the model finds the name Pip as well as Mr. Pip then we’d like to count this as one character and not two.

Evaluating results

At the evaluation stage of such a project it would be ideal to have a labelled dataset against which to compare each set of results but our books are not labelled so this avenue was unavailable.

Typical metrics that one would use in a task like this are precision and recall:

> Of all the characters we identified, how many are valid?

> Of the characters that we should have identified, how many did we get?

Below are some illustrative examples of what would constitute a true positive (TP), false positive (FP) and false negative (FN) for this task:

- TP example: Alice is correctly identified as a character in Alice in Wonderland

- FP example: Dear is incorrectly identified as a character in Alice in Wonderland

- FN example: White Rabbit fails to be identified as a character in Alice in Wonderland

Given that I wanted to ‘operationalize’ this process, I needed to find an independent source from which I could extract character information to compare against in a slightly more systematic way.

One such source is Wikidata: a human- and machine-readable knowledge base which ‘acts as central storage for the structured data of its Wikimedia sister projects including Wikipedia’ (Wikidata, 2021). What I opted to do was retrieve character information from Wikidata and compare their character lists with my character lists. Wikidata character lists are not exhaustive, nor is the level of detail standardized. Without exhaustive character lists, it was not possible to automate the calculation of precision, but I did review the top 20 characters extracted based on my knowledge of the books (they were all childhood favourites!) to arrive at an indication of precision. Calculating recall against the Wikidata lists was possible, but again the metric was slightly flawed: for Great Expectations only 6 extremely main characters were listed (there are actually many more prominent characters than this in the book), where for Little Women 61 characters were listed (many of whom are extremely incidental to the plot).

The project has demonstrated reasonable success in extracting the main characters from novels, including the previously unseen novel Jane Eyre. Precision and recall were both surprisingly high:

Great Expectations:

- Precision: 0.93

- Recall: 1.0

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland:

- Precision: 0.90

- Recall: 0.95

Little Women

- Precision: 0.78

- Recall: 0.48

Jane Eyre:

- Precision: 0.83

- Recall: 1.0

Recall was clearly influenced by the variable number of characters listed by our ‘source of truth’ Wikidata. Nonetheless, the majority of characters in the Top 20 were valid and made sense.

Using proper nouns as the main method of identifying character names worked well to ensure we got the full name in most cases. Loosely ‘ensembling’ this with the results of the more conventional named entity recognition processes helped to reduce some of the noise in the proper nouns (which did not only include persons but also other types of entities). Leveraging the expected long-tailed distribution of characters ensured that we pruned off more of the noisy ‘non-characters’ as well as minor and relatively unimportant characters. Grouping names worked to the extent that we could identify closely-related names like Pip and Mr. Pip, but was less than perfect when it came to more complex scenarios like families where multiple characters all share the same surname.

Exploring literary questions

Having laid all this groundwork we would now be in a position to explore questions like the following:

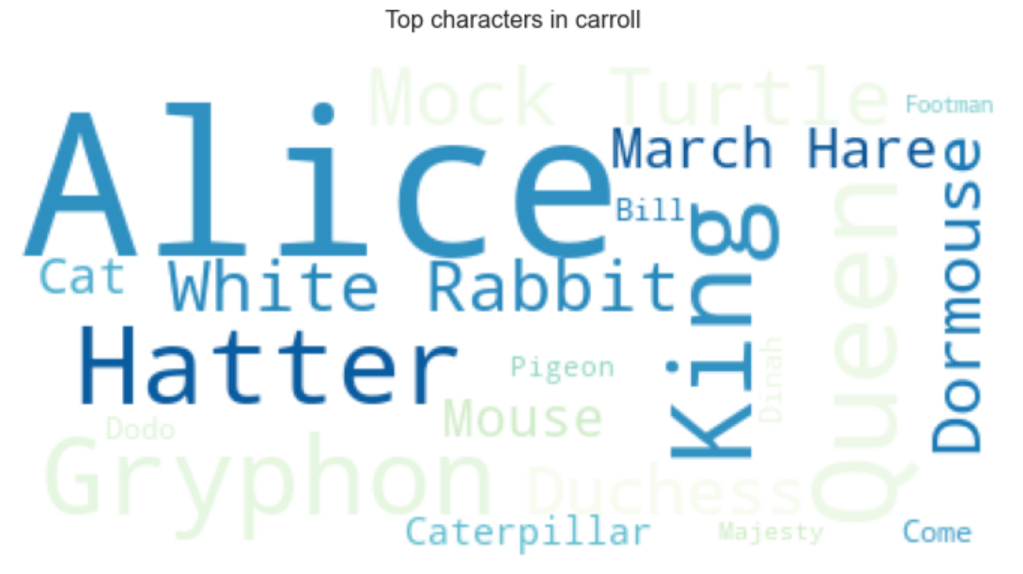

- How prominent is each character in terms of mentions?

- A wordmap is always a fun way to make this kind of information more real:

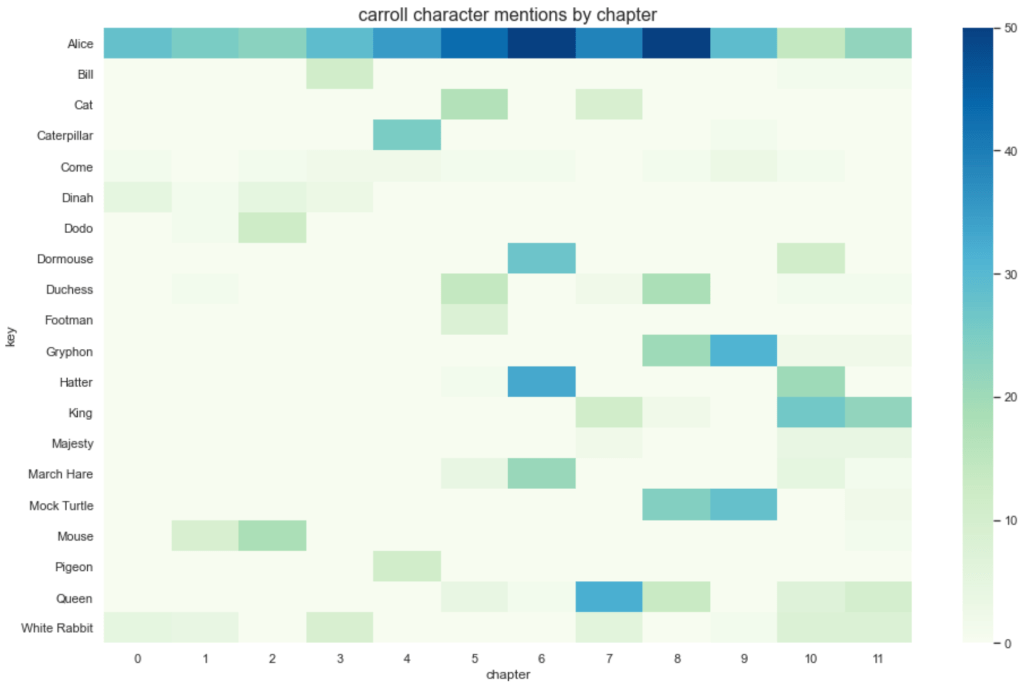

- Are characters a sustained presence or do they come and go?

In Alice in Wonderland, being a children’s story, the procession of characters is quite clear and simple. Alice is strong throughout (this is her story after all). We can also see key groupings, for example, in the seventh chapter (labelled 6 below as counting started from 0) we see Alice, the March Hare, the Hatter and Dormouse gathered together for the famous ‘Mad Hatters Tea Party’.

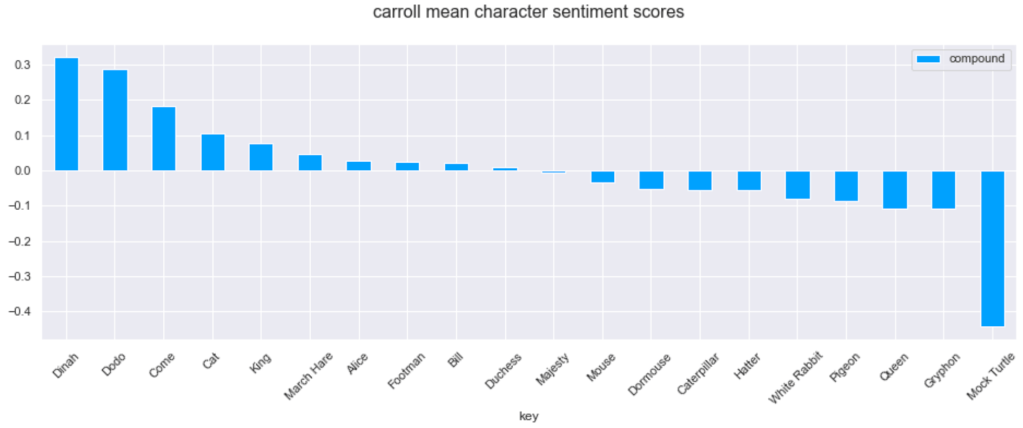

- How might we feel about each character in terms of sentiment analysis?

I used the NLTK implementation of vader as a quick and simple sentiment analysis algorithm. According to the example usage documentation (Hutto, 2020) vader works best at sentence level and it was suggested that multiple sentences could be averaged to arrive at an overall sentiment score. This compound score with a range between -1 (extremely negative) and +1 (extremely positive) is what I used.

Alice in Wonderland has the most even spread of positive and negative characters: the extreme positive being Alice’s beloved cat Dinah and the extreme negative being the melancholy Mock Turtle make sense.

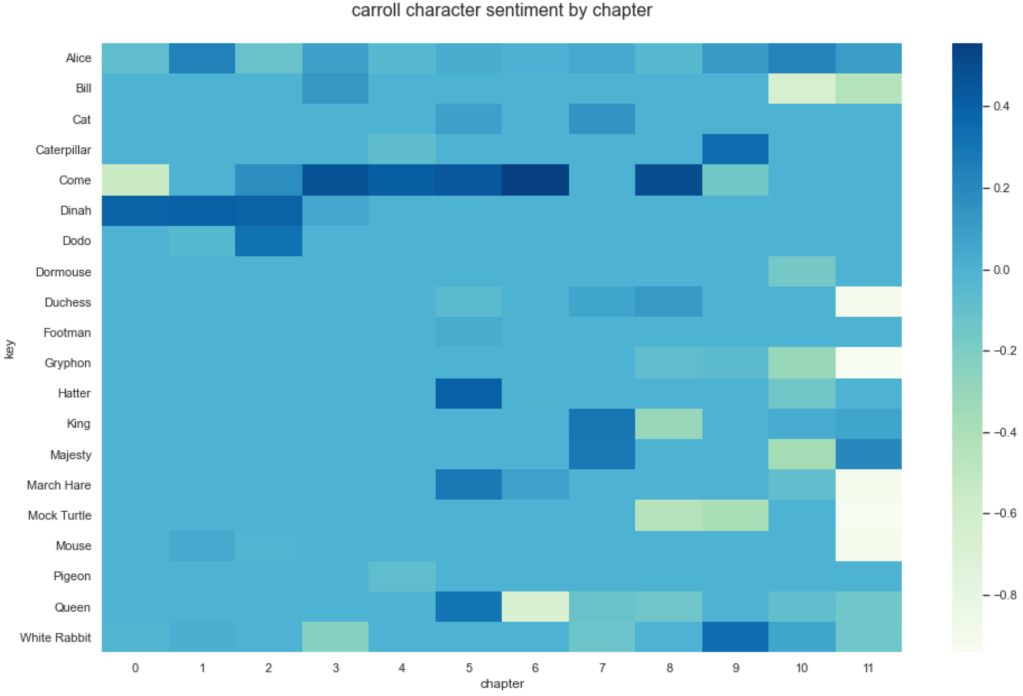

- How do sentiments around characters change through the chapters?

Using a heatmap to visualize this kind of information makes it easy to spot patterns and anomalies.

What was interesting about Alice in Wonderland was to notice how much negativity appears in the final chapter around certain characters: this is the trial scene where, supposedly, it will be determined who stole the tarts. The whole chapter essentially descends into greater levels of chaos as it proceeds, with characters either being aggressive, irritating or irrational – so this negativity we see makes sense.

The code

If you’d like to have a look at the code in detail, you can access it here in my Github repo: