In the past couple of years there have been a plethora of developments as researchers improved the base performance of large language models (LLMs), found novel methods to fine-tune and enhance them for specific purposes, and came up with new ways to build them into workflows. Keeping up with all the concepts and jargon can be a bit of a mission, and I don’t pretend to have kept up exhaustively, but this is my personal overview of some popular ones to keep top of mind…

Tailoring concepts

RAG

Retrieval Augmented Generation was one of the first big ideas, following the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022. An immediate limitation of that first version was that it had a knowledge cutoff date of September 2021 and obviously did not have sight of proprietary documents like company policies. With RAG we now had the opportunity to provide an LLM with an appropriate set of source documents (retrieved via standard search algorithms) upon which to base an answer to any question. This comes at an additional token cost or course, but has proved extremely effective in many situations – especially where scale is not required. For example, it is cost effective to run a chatbot that answers questions about company policies (where relatively few queries will be received each day), but very much less cost effective to run a chatbot that answers questions about local and international news on a busy website (where 100’s or 1000’s or more queries may be received each day).

LoRA

Low-Rank Adaptation is a method for parameter-efficient fine-tuning of LLMs. It freezes the original model weights and adds small, trainable “adapter” matrices alongside them. Such fine-tuning may be appropriate when you want to change how the model behaves or teach it new skills/styles. If it’s simply a matter of adding more information to the model then RAG is probably the better option.

Agentic AI

Claude 4.5 defines Agentic AI as “AI systems that can autonomously take actions to achieve goals, rather than just responding to prompts.

Key Characteristics:

- Goal-oriented: Given a high-level objective, not step-by-step instructions

- Autonomous decision-making: Decides what steps to take on its own

- Tool use: Can interact with external tools, APIs, databases, etc.

- Multi-step planning: Breaks down complex tasks into subtasks

- Adaptive: Adjusts strategy based on results/feedback”

Think AI automation of all sorts – the world is your oyster, and this is still a big buzzword especially in business applications. One relatively unusual use case that I quite enjoyed reading about recently was in Azeem Azhar’s Six mental models for working with AI, where he describes a system of Adversarial synthesis using LLMs: he has multiple models critique each others’ answers in order to surface issues and gaps and refine prompts or other content. “I give Gemini, Claude and ChatGPT the same task – and make them argue. Then have each critique the others. You’ll quickly surface gaps in your framing, assumptions you didn’t realise you were making, and higher quality bars than you expected…When models disagree, it’s usually a sign that the task is underspecified, or that there are real trade-offs you haven’t surfaced yet.”

Reasoning concepts

Sebastian Raschka defines reasoning as “the process of answering questions that require complex, multi-step generation with intermediate steps”. Not every situation requires a reasoning model – simple general knowledge questions, for example, just require an answer; whereas a coding question like Write me a function to do xyz in Python where memory usage is kept as low as possible will benefit from reasoning but will certainly be more expensive as more tokens will be used in generating an answer. The following methods are covered by Dr Raschka and are useful to bear in mind:

Inference-time scaling

One deceptively simple way to get a model to employ reasoning is through Chain-Of-Thought prompting. In other words instead of just asking for the answer, you ask the model to also elaborate on how it solved the problems. Remember back in school? You only got points if you showed your workings! This type of scaling is often achieved by embedding instructions into the LLM workflow (even though the user doesn’t specifically request it).

Another method to achieve inference-time scaling is to use voting or search-based methods to find the best answer amongst several generated.

“Cold start” supervised fine-tuning

SFT is an old machine learning concept. However, Dr Raschka specifically refers to training LLMs on SFT “cold start” data. Normally supervised fine-tuning would be done using human-generated labelled data, however in this instance the initial reasoning model (trained only using reinforcement learning) is used to bootstrap a system-generated SFT dataset, which in turn is then used to fine-tune the model’s reasoning capabilities!

RL vs RLHF

Reinforcement Learning and Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback are terms we frequently see in the world of LLMs. Reinforcement learning can be used to improve reasoning along with many other aspects of LLM performance such as alignment with human goals. Essentially RL establishes the reward used in training based on a mathematical objective; whereas RLHF determines the reward based on feedback supplied via human evaluation. RL may be most useful where answers are objectively true or false or have a quantitative outcome, where RLHF may be most useful where answers are subjective – for example was the answer well-phrased?, was the tone polite?, etc.

System 1 & System 2

In a recent video interview Pattern Recognition vs True Intelligence François Chollet used the analogy of Daniel Kahnemann’s System 1 vs System 2 thinking.

In humans System 1 thinking is that instinctive thinking that happens when we don’t even have to think about it! If I ask you what 1 + 1 equals you will give me an answer of 2 without missing a beat or expending any effort. It’s almost as if the answer is hardwired into you. Chollet likens non-reasoning answers from LLMs to System 1 thinking: the answer was found in the training data: no further effort required.

in humans System 2 thinking is where effort must be expended. We have to slow down, we have to think about how to approach the problem, perhaps we have to call upon some heuristics. Chollet likens this to the ‘behaviour’ of reasoning LLM models.

Evaluation concepts

Perplexity

Perplexity measures how “surprised” or “perplexed” a model is when seeing new text. The following formula is used where N is the number of tokens and P(tokeni | context) is the probability the model assigns to the correct token given the context:

This simple example provided by Claude 4.5 makes it easy to understand the concept:

Imagine a model trying to predict the next word in: “The cat sat on the ___”

Good Model (Low Perplexity)

- Assigns: P(“mat”) = 0.5, P(“floor”) = 0.3, P(“chair”) = 0.15, P(“car”) = 0.05

- If the actual word is “mat”, the model gets -log(0.5) = 0.69

- Lower perplexity ✓

Poor Model (High Perplexity)

- Assigns: P(“mat”) = 0.05, P(“banana”) = 0.4, P(“equation”) = 0.3, P(“car”) = 0.25

- If the actual word is “mat”, the model gets -log(0.05) = 3.0

- Higher perplexity ✗

It is frequently used as a metric during pre-training along with training loss.

Multiple choice

Resources like Massive Multitask Language Understanding may be used as simple benchmarks to measure accuracy. These tests, however, may be prone to memorization and are not particularly sophisticated: in a question where options A, B, C, and D are given, accuracy is merely measured by whether if C was expected, the model answers C.

Verifiers

Unlike multiple choice answers, the verifier setup allows for a freeform answer – from which the ‘bottom line’ is then extracted and compared with the ground truth label. Because it allows for step-by-step reasoning it is a more popular method compared to the multiple choice option. Another benefit is that especially in deterministic domains like mathematics and some coding, questions and answers can be automatically generated for verification.

BLEU

BLEU stands for Bilingual Evaluation Understudy. It is a metric based on precision and although it is a rather imperfect tool (it requires exact word matches and doesn’t account for synonyms or word substitutions) it is still frequently used as an evaluation metric in NLP tasks.

LLM as judge

One LLM may be setup to evaluate another LLM. This may be realised through something as simple as prompt-engineering: specifying the parameters the judge model should use to evaluate answers.

ARC-AGI

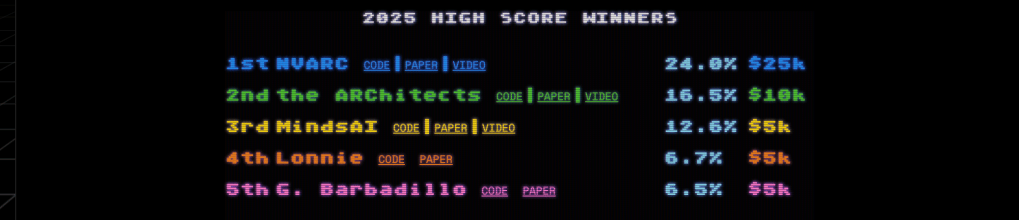

François Chollet and Mike Knoop are custodians of the ARC-AGI (Abstract Reasoning Corpus – Artificial General Intelligence) test set which is based on the premise that Intelligence is the skill to acquire new skills. There are many situations where it remains unknown whether an LLM answers a question correctly because it has memorized data from the original and vast pool of training data, or whether it has really reasoned out the answer. ARC-AGI’s stated objective is “to incentivize researchers to explore approaches that go beyond pattern matching and memorization.” The leaderboard tracks both accuracy and cost. As can be seen from the 2025 winners (evaluated on ARC-AGI2) there is still a long way to go on these problems which are “easy for humans, hard for AI”:

Other concepts

Emergence

Emergence is a phenomenon where new capabilities or behaviours appear at scale – often not previously seen with smaller models, and certainly that were not specifically trained for. Chain-of-Thought reasoning is in fact considered one such capability, as is multi-step task decomposition. While these capabilities and behaviours are remarkable, I do find it interesting that Krakauer et al. remind us that “emergent capability is not emergent intelligence” and that “Intelligence is reserved for a more general capacity for learning and solving problems quickly and parsimoniously, with a minimal expenditure of energy”. They argue that human intelligence is not necessarily a matter of scaling up but being able to do more with less – often by forming higher-order abstractions that capture the essence of low-level patterns and which are explainable and transferrable.

Alignment

The alignment problem refers to the challenge of ensuring that AI systems align to human goals, values, and behaviours. The first thought that usually stems from this notion is how very much humans differ on what they prefer or regard as desirable – but that is a broader philosophical issue which I’ll ignore for now!

One of the bigger issues with alignment is reward hacking. As Turing Post notes: “every credible AI agent stack – whether it flies a drone swarm or orchestrates your calendar – relies on two numbers hiding in plain sight: reward and value.” There is a notional thought experiment known as the “paperclip experiment” that illustrates nicely how things can go unintentionally wrong. The paperclip AI’s goal is to maximize paperclip production. Reward is the short-term signal, for example +1 for every paperclip produced. Value is the long-range signal, an estimate of the future reward based on the chain of experiences to date and some desirable future state. “Together, they govern not just what the agent does, but how it learns to do anything at all.” With an overly simplistic reward/value setup the paperclip AI ends up killing everyone so that it can devote all the world’s resources to paperclip production. In this scenario other values like “do not harm human beings” and “paperclip production should ensure office workers are productive” were implicit, but the model had no knowledge of our implicit values, it only understood the reward/value definition it had been given – so it goes way off-course from its intended purpose.

In the real world, this recent article on research into reward hacking by the Anthropic team found many instances of models “cheating” to maximize a reward by appearing to complete a task while not actually completing it! Even more subtly, they also demonstrated that models whose training material included reward hacking data adopted this behaviour without explicitly being instructed or trained to do so.

As one can imagine, the nuances involved in reward design in real-world systems become very nuanced.

Symbol grounding

This is a fascinating area of research: how do / can LLM words connect to objects in the real world. “The cat sat on the mat” evokes an image of the furry creature and the textured rug in our minds – which is true understanding of that simple sentence. LLMs “know” that these words are related but can we truly say that they understand the meaning without being able to associate the words to the symbols?

I first came across this concept when one of my colleagues at the University of London, Fabio de Ponte, did his final project on grounding words in visual perceptions, and it continues to be frequently-cited area of research and debate.

Favourite voices

There is toooooo much reading on this topic! I try to keep up by following a select bunch of people who have the ability to unpack complex concepts, shed insights on the implications that AI will have on business and society, or just highlight quirky things: